The Energy Consulting Group

Business strategy for upstream oil and gas producers and service companies

| Owowo Discovery: Reported to potentially have as much as 1 billion of recoverable resources. | |

| Nigeria Oil and Gas Overview | |

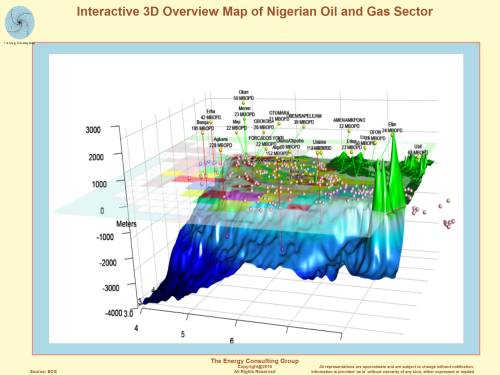

| (We have also prepared a 3D interactive map of the Nigerian oil sector map showing water depths, field locations, and production volumes for selected oil fields. If interested in such an analysis, go here. |

====================================================================================================================================================

Nigeria: Country Overview

(source: EIA)

EIA Overview

Nigeria is the largest oil producer in Africa and was the world's fourth leading exporter of LNG in 2012. Despite the relatively large volumes it produces, Nigeria's oil production is hampered by instability and supply disruptions, while the natural gas sector is restricted by the lack of infrastructure to monetize gas that is currently flared (burned off).

Nigeria is the largest oil producer in Africa, holds the largest natural gas reserves on the continent, and was the world's fourth leading exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in 2012. Nigeria became a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1971, more than a decade after oil production began in the oil-rich Bayelsa State in the 1950s. Although Nigeria is the leading oil producer in Africa, production suffers from supply disruptions, which have resulted in unplanned outages as high as 500,000 barrels per day (bbl/d).

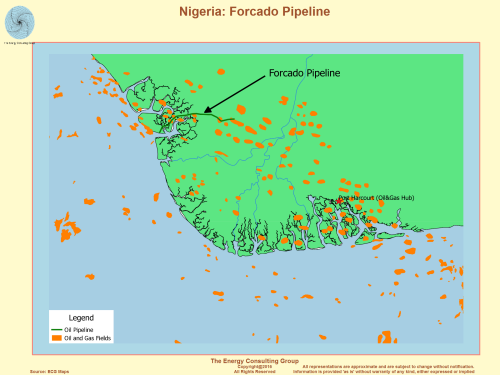

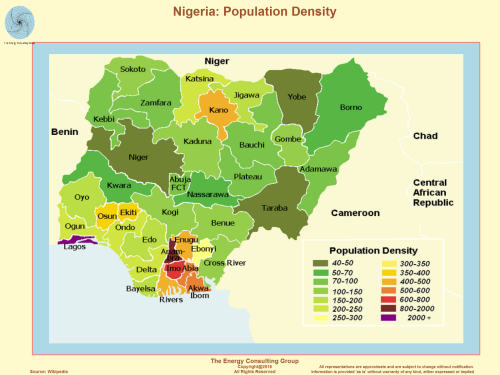

The oil and natural gas industries are primarily located in the Niger Delta region, where it has been a source of conflict. Local groups seeking a share of the wealth often attack the oil infrastructure, forcing companies to declare force majeure (a legal clause that allows a party to not satisfy contractual agreements because of circumstances that are beyond their control that prevent them from fulfilling contractual obligations) on oil shipments. At the same time, oil theft, commonly referred to as "bunkering," leads to pipeline damage that is often severe, causing loss of production, pollution, and forcing companies to shut in production.

Aging infrastructure and poor maintenance have also resulted in oil spills. Also, natural gas flaring, the burning of associated natural gas that is produced with oil, has contributed to environmental pollution. Protest from local groups over environmental damages from oil spills and gas flaring have exacerbated tensions between some local communities and international oil companies (IOCs). The industry has been blamed for pollution that has damaged air, soil, and water, leading to losses in arable land and decreases in fish stocks.

Nigeria's oil and natural gas resources are the mainstay of the country's economy. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that oil and natural gas export revenue accounted for 96% of total export revenue in 2012. For 2013, Nigeria's budget is framed on a reference oil price of $79 per barrel, providing a wide safety margin in case of price volatility. Savings generated when oil revenues exceed budgeted revenues are placed into the Excess Crude Account (ECA), which can then be drawn down in years when oil revenues are below budget, according to the IMF.

Source: U.S. Department of State

Total primary energy consumption

EIA estimates that in 2011 total primary energy consumption was about 4.3 quadrillion British thermal unit (Btu). Of this, traditional biomass and waste (typically consisting of wood, charcoal, manure, and crop residues) accounted for 83%. This high share represents the use of biomass to meet off-grid heating and cooking needs, mainly in rural areas. World Bank data for 2010 indicate that electrification rates for Nigeria were 50% for the country as a whole - leaving approximately 80 million people in Nigeria without access to electricity.

Management of the oil and natural gas sectors

The Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB), which was initially proposed in 2008, is expected to change the organizational structure and fiscal terms governing the oil and natural gas sectors, if it becomes law. IOCs are concerned that proposed changes to fiscal terms may make some projects commercially unviable, particularly deepwater projects that involve greater capital spending.

The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) was created in 1977 to oversee the regulation of the oil and natural gas industries, with secondary responsibilities for upstream and downstream developments. In 1988, the NNPC was divided into 12 subsidiary companies to regulate the sub-sectors within the industry. The Department of Petroleum Resources, within the Ministry of Petroleum Resources, is another key regulator, focusing on general compliance, leases and permits, and environmental standards.

Currently, the majority of Nigeria's major oil and natural gas projects are funded through joint ventures (JV) between international oil companies (IOCs) and NNPC, where NNPC is the majority shareholder. The rest of the contracts are managed through production sharing contracts (PSCs) with IOCs. PSCs are the fiscal regime typically, but not always, governing deepwater projects and contain more attractive terms than those in JV arrangements, the fiscal regime typically governing onshore/shallow water projects. PSC terms on deepwater projects tend to be more favorable to incentivize the development of deepwater projects.

The Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB), which was initially proposed in 2008, is expected to change the organizational structure and fiscal terms governing the oil and natural gas sectors, if it becomes law. IOCs are concerned that proposed changes to fiscal terms may make some projects commercially unviable, particularly deepwater projects that involve greater capital spending. Some of the most contentious areas of the PIB are the potential renegotiation of contracts with IOCs, changes in tax and royalty structures, deregulation of the downstream sector, restructuring of NNPC, a concentration of oversight authority in the Minister of Petroleum Resources, and a mandatory contribution by IOCs of 10% of monthly net profits to the Petroleum Host Communities Fund.

The latest draft of the PIB was submitted to the National Assembly by the Ministry of Petroleum Resources in July 2012. The delay in passing the PIB has resulted in less investment in new projects as there has not been a licensing round since 2007, mainly because of regulatory uncertainty. The regulatory uncertainty has also slowed the development of natural gas projects as the PIB is expected to introduce new fiscal terms to govern the natural gas sector.

International oil companies

The major international players in Nigeria's oil and natural gas sectors are Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Total, and Eni. IOCs participating in onshore and shallow water oil projects in the Niger Delta region have been affected by the instability in the region. As a result, there has been a general trend for IOCs to sell their interests in onshore oil projects.

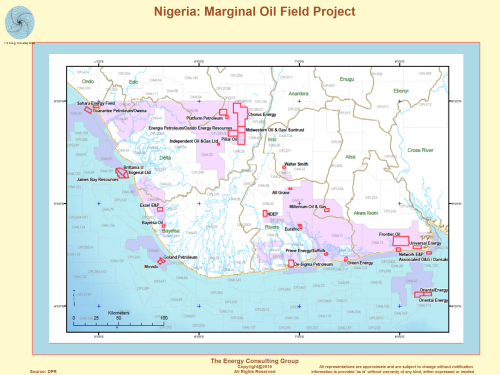

NNPC has JV arrangements and/or PSCs with Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Total, and Eni. Other companies active in Nigeria's oil and natural gas sectors are Addax Petroleum, ConocoPhillips, Petrobras, Statoil, and several Nigerian companies. IOCs participating in onshore and shallow water oil projects in the Niger Delta region have been affected by the instability in the region. As a result, there has been a general trend for IOCs to sell their interests in marginal onshore and shallow water oil fields, mostly to Nigerian companies and smaller IOCs, and focus their investments on deepwater offshore projects and onshore natural gas projects. Nigeria plans to have a licensing round for marginal onshore and shallow water fields in 2014. The licensing round will consist of 31 fields being sold off by IOCs, according to IHS CERA. IOCs divesting from some of these projects include Shell, ConocoPhillips, and Chevron.

ShellShell has been working in Nigeria since the 1930s. Shell operates in Nigeria through the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Limited (SPDC) and the Shell Nigeria Exploration and Production Company Limited (SNEPCo). SPDC is one of the largest oil and gas companies in Nigeria. SPDC has a JV with NNPC that is made up of NNPC (55%), Shell (30%), Total Exploration and Production Nigeria Limited (10%), and Nigerian Agip Oil Company Limited (Eni) (5%). SPDC's operations include a network of pipelines, eight gas plants, and two oil export terminals.

Shell's offshore activities are carried out by SNEPCo, which was formed in 1993 to develop Nigeria's deepwater offshore oil and gas resources. Under a PSC with NNPC, SNEPCo owns shares in three deepwater blocks: Bonga (Shell-operated), Erha/Erha North (ExxonMobil-operated), and Zabazaba/Etan (Eni-operated).

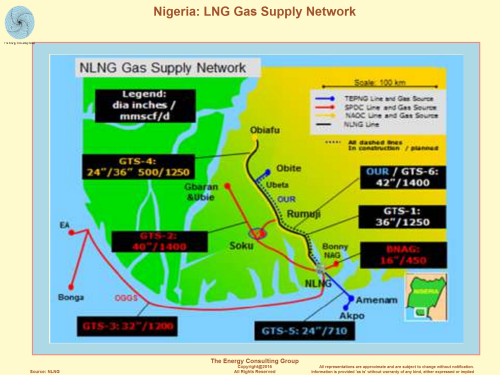

Shell, through its subsidiary Shell Gas B.V., holds a 25.6% interest in Nigeria LNG Limited (NLNG). NLNG operates six liquefaction trains at the Bonny facility with a total capacity of 22 million tons per annum (MMtpa), or 1,056 billion cubic feet per year (Bcf/y). Gas supplies for the LNG facility come from several oil and gas fields operated by Shell, along with fields operated by the other NLNG partners, Total and Eni. Shell provides the LNG facility with fuel from its onshore projects Gbaran-Ubie, Soku, and Bonny and its offshore projects Bonga and EA.

Shell's onshore oil production has been affected by the instability in the Niger Delta region. Shell has temporarily shut in portions of its production several times over the past decade, while declaring force majeure on oil shipments, as a result of frequent sabotage to pipelines. Some of Shell's onshore/shallow water oil production capacity still remains shut in.

From 2010 to mid-2013, Shell, through SPDC, has sold its share in eight onshore licenses. In June 2013, Shell announced that it would initiate a strategic review to consider the potential divestment in the interests it holds in some onshore leases in the eastern Niger Delta. The company also indicated that it may sell its share in major pipelines. Shell has not indicated any plans to sell its deepwater offshore oil projects or its onshore natural gas projects in Nigeria.

ExxonMobilExxonMobil operates in Nigeria through its subsidiary Mobil Producing Nigeria (MPN) with a JV arrangement with NNPC. MPN has a 40% stake in the JV, and NNPC holds the remaining 60%. ExxonMobil also operates in Nigeria through its affiliate Esso Exploration and Production Nigeria Limited (EEPNL), which has a PSC with NNPC.

Most of ExxonMobil's projects are located in the deepwater offshore,

making them less vulnerable to oil theft attempts. The company's largest

assets in Nigeria include Qua Iboe, which is a crude blend produced from

several offshore fields in the Bight of Bifra, and the Erha/Erha North

deepwater project. Qua Iboe is Nigeria's largest exported crude blend, and

production averages around 400,000 bbl/d, according to ExxonMobil.

ExxonMobil also holds a 30% interest in Nigeria's newest producing deepwater

field Usan, which is operated by Total. ExxonMobil produces natural gas

liquids from the Oso Natural Gas Liquids project and the East Area Natural

Gas Liquids project 2.

Chevron, through its subsidiary Chevron Nigeria Limited, holds a 40% interest in 13 concessions under its JV arrangement with NNPC. Chevron produces natural gas and the Escravos crude oil blend from several onshore and shallow water fields located in the Niger Delta. The pipeline network transporting Escravos crude is often subject to pipeline damage from oil theft. As a result, Chevron announced in June 2013 that it will sell its 40% interests in five onshore/shallow water leases.

Chevron, like its counterparts, is focused on deepwater offshore projects and onshore natural gas projects. Some of Chevron's largest oil projects are the Agbami field off the coast of the Niger Delta, which it operates, and the Usan deepwater field operated by Total, which Chevron owns a 30% share. The company also plans the start-up of the 33,000-bbl/d Escravos Gas to Liquids (GTL) plant, which is expected to come online within a year. Chevron is also the largest shareholder (36.7%) of the West African Gas Pipeline Company Limited, which owns and operates the West African Gas Pipeline. The pipeline transports gas from Nigeria to customers in Benin, Togo, and Ghana.

In 2012, Chevron restored natural gas production at some of its onshore leases. The Onshore Asset Gas Management (OAGM) project consists of the restoration of facilities that were destroyed in 2003 during civil unrest. It includes six onshore fields, and it is designed to supply the domestic market with 125 million cubic feet per day (MMcf/d) of natural gas.

TotalTotal has participated in Nigeria's oil and natural gas industries since the 1960s and currently has multiple subsidiaries that participate in the oil and gas sectors. Total operates mostly deepwater offshore fields and a smaller number of onshore fields that are linked to Shell's Bonny export terminal. Some of Total's largest projects include the Amenam, Akpo, and Usan deepwater oil fields.

Natural gas is also produced at onshore fields, known as the Obite Gas Project, and it is sent to Nigeria's LNG plant at Bonny. Associated gas from the offshore Amenam field is also transported to the Bonny LNG plant, and the field is the hub of Total's gas supply network to the LNG facility. Total owns a 15% stake in NLNG, the company that operates the LNG plant at Bonny.

Total also has a 17% interest in Brass LNG Limited, a consortium that is

building the Brass LNG Liquefaction Complex. According to Total, engineering

work is still in progress. The complex is expected to have two liquefaction

trains with a total capacity of 10 MMtpa (480 Bcf/y). The other members in

the consortium include NNPC (49%), ConocoPhillips (17%), and Eni (17%).

Eni, through its subsidiary Agip, produces oil in both onshore and offshore areas of the Niger Delta region. According to Eni, its operations are regulated by PSCs and concession contracts. A large portion of Eni's production comes from onshore fields that produce the crude oil blend called Brass River. A portion of Brass River is lost regularly to pipeline damage and oil theft. As a result, Eni has shut in varying volumes of production since 2006. In 2012, Eni divested its 5% stake in three oil leases.

Eni owns a 10.4% share in NLNG and a 17% share in Brass LNG Limited. The company participates in a number of onshore gas projects, including the Tuomo gas field, Gbaran-Ubie, and the Idu project, most of which feed the Bonny LNG facility. The company recently reduced the amount of gas it flared in Nigeria. According to Eni's 2012 annual report, 90% of the associated gas it produced in Nigeria was sold.

Oil

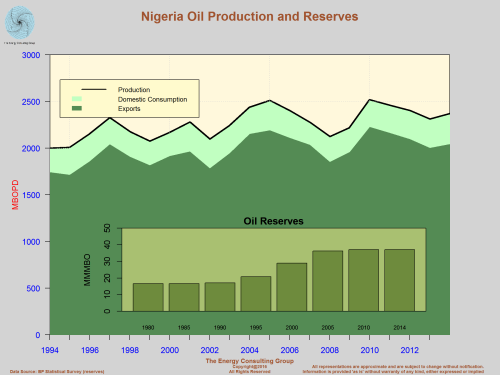

Nigeria has the second largest amount of proven crude oil reserves in Africa, but reserve estimates have been stagnant as exploration activity has been low. Rising security problems coupled with regulatory uncertainty have contributed to decreased exploration activity.

According to Oil & Gas Journal (OGJ), Nigeria has an estimated 37.2 billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves as of January 2013 — the second largest amount in Africa, after Libya. The majority of reserves are found along the country's Niger River Delta and offshore in the Bight of Benin, the Gulf of Guinea, and the Bight of Bonny. Current exploration activities are mostly focused in the deep and ultra-deep offshore with some activities in the Chad basin, located in the northeast of the country.

Nigeria's proven crude oil reserve estimates have been stagnant. According to IHS CERA, the government hopes to increase proven crude oil reserves to 40 billion barrels over the next few years, but with exploration activity levels at their lowest in a decade, this goal will be challenging to achieve. Rising security problems related to oil theft, pipeline sabotage, and piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, coupled with investment uncertainties surrounding the long-delayed PIB, have contributed to less exploration activity, particularly onshore, and will most likely continue to hinder the country from reaching its oil production target of 4 million bbl/d.

Production and consumption

Crude oil production in Nigeria reached its peak of 2.44 million bbl/d in 2005, but began to decline significantly as violence from militant groups surged, forcing many companies to withdraw staff and shut in production. Oil production recovered somewhat after 2009-2010 but still remains lower than its peak because of ongoing supply disruptions.

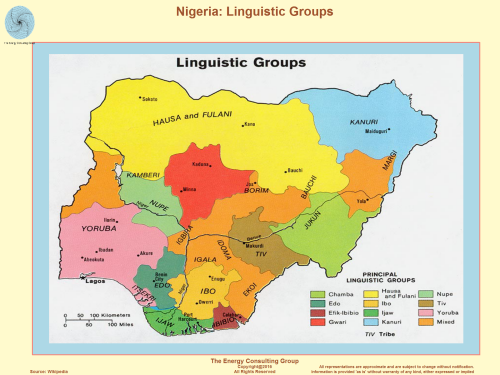

Nigeria produces mostly light, sweet (low sulfur) crude oil of which the vast majority is exported to global markets. Crude oil production in Nigeria reached its peak of 2.44 million bbl/d in 2005, but began to decline significantly as violence from militant groups surged, forcing many companies to withdraw staff and shut in production. By 2009, crude oil production plummeted by more than 25% to average 1.8 million bbl/d. The lack of transparency of oil revenues, tensions over revenue distribution, environmental damages from oil spills, and local ethnic and religious tensions created a fragile situation in the oil-rich Niger Delta.

In late 2009, amnesty was declared, and the militants came to an agreement with the government whereby they handed over weapons in exchange for cash payments and training opportunities. The rise in oil production after 2009 was partially due to the reduction in attacks on oil facilities following the implementation of the amnesty program, which allowed companies to repair some damaged infrastructure and bring some supplies back online.

Another major factor that contributed to the upward trend in output was the continued increase in new deepwater offshore production. The government took measures to attract investment to deepwater acreage in the 1990s to boost production capacity and diversify the location of the country's oil fields. To incentivize investments in deepwater areas, which involve higher capital and operating costs, the government offered PSCs in which IOCs received a greater share of revenue as the depth increased. The first deepwater field began production in 2003, and since then, output from deepwater fields has added more than 800,000 bbl/d to the country's production capacity.

Although the amnesty program and new deepwater fields contributed to production gains, Nigeria's crude oil production began to decline again after 2011. Despite the start of the Usan deepwater oil field in February 2012, crude oil production in Nigeria slightly decreased from 2.13 million bbl/d in 2011 to 2.10 million bbl/d in 2012. Supply disruptions throughout the year and heavy floods in the fourth quarter of 2012 were the main reasons for the year-over-year decline.

Supply disruptions escalated in 2013, mostly stemming from pipeline

damages associated with oil theft, which resulted in the shut-in of the

Trans Niger Pipeline and Nembe Creek Trunkline and force majeure on the

shipments of multiple crude grades. From January to November 2013, crude oil

production averaged slightly below 2.0 million bbl/d, similar to the levels

in 2008-2009 when disruptions hit record highs.

Security risks

The instability in the Niger Delta has resulted in significant amounts of shut-in production at onshore and shallow offshore fields, forcing companies to frequently declare force majeure on oil shipments. Supply disruptions escalated in 2013 and from January to October 2013 crude oil production averaged slightly below 2.0 million bbl/d, similar to the levels in 2008-2009 when disruptions hit record-highs.

Since the mid-2000s, Nigeria has experienced increased pipeline vandalism, kidnappings, and militant takeovers of oil facilities in the Niger Delta. The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) has been one of the main groups attacking or threatening attacks on oil infrastructure for political objectives, claiming to seek a redistribution of oil wealth and greater local control of the sector.

Security concerns have led some oil services firms to pull out of the country and oil workers' unions to threaten strikes over security issues. The instability in the Niger Delta has also resulted in significant amounts of shut-in production at onshore and shallow offshore fields, forcing companies to frequently declare force majeure on oil shipments.

The amnesty program implemented in 2009 led to decreased attacks and supply disruptions in 2009-2010, and some companies were able to repair damaged oil infrastructure. However, the lack of progress in job creation and economic development has contributed to increased bunkering and other attacks in recent years.

Bunkering, in the context of Nigeria's oil industry, refers to the theft and trade of stolen oil. According to information disseminated by an investigative task force in Nigeria, there are three main ways oil is bunkered: by small cargo canoes that navigate the swampy, shallow waters of the Niger Delta where culprits puncture pipelines to siphon crude into small tanks; stealing crude directly from the wellhead; or filling tankers at export terminals, which is referred to as "white collar" bunkering.

Some stolen oil is taken to illegal refineries along the Niger Delta's swampy bush areas and sold domestically and regionally, while other portions make their way to the international market. Nigeria is estimated to have lost $10.9 billion in revenues through oil theft from 2009â�2011, according to Nigeria's Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, a government-funded body.

Environmental damages

Pipeline sabotage from oil theft and poorly maintained, aging pipelines have caused oil spills. The oil spills have resulted in land, air, and water pollution, severely affecting surrounding villages by decreasing fish stocks and contaminating water supplies and arable land.

The Niger Delta region suffers from environmental damage caused by pipeline sabotage from oil theft and also spills from illegal refineries. Poorly maintained, aging pipelines are also a reason behind oil spills as this can result in pipeline ruptures as they corrode. The amount spilled because of oil theft versus aging infrastructure and/or operational failures is highly debated among oil companies and environmental and human rights groups.

The oil spills have caused land, air, and water pollution, severely affecting surrounding villages by decreasing fish stocks and contaminating water supplies and arable land. The United Nations Environment Program released a study on Ogoniland and the extent of environmental damage from more than 50 years of oil production in the region. The study confirmed community concerns regarding oil contamination across land and water resources, stating that that the damage is ongoing and estimating that it could take 25 to 30 years to repair.

Methodology matters

Nigerian oil production estimates are often different among organizations and can range widely. The main reasons underlying the differences are the methods used to measure supply disruptions and the classification of crude and condensate.

Oil production estimates for Nigeria can vary widely among the country's government officials, global consulting firms, and other international organizations. The main reasons underlying the different estimates are the methods used to measure supply disruptions and the classification of crude and condensates.

EIA estimates that unplanned supply outages to Nigeria's oil production typically range from 100,000 to 500,000 bbl/d. The methodology employed to measure disruptions can be different across sources and largely depends on production capacity estimates. EIA uses the concept of effective production capacity, defined as the amount of production that could come back to markets within a year, to measure Nigeria's unplanned outages. It takes into account permanent and/or prolonged production loss due to the degradation of shut-in oil fields and damages to operational components that would take longer than a year to repair, which is dependent on the financial, security, and political situations.

A large portion of Nigeria's oil production, around 350,000 to 400,000 bbl/d, may be considered to be condensate (a higher API gravity) depending on the qualification on the API scale. The qualification used to classify crude and condensate differs across countries and organizations that forecast oil production. As a result, crude oil production estimates may vary depending on crude oil quality distinctions. For example, EIA estimates that total oil production in Nigeria averaged slightly more than 2.5 million bbl/d in 2012, of which 2.1 million bbl/d was crude oil and most of the remainder was condensate with an API gravity higher than 46 degrees. A smaller amount of the total oil produced in Nigeria is also natural gas liquids.

Upcoming projects

There are several planned oil and gas projects scheduled to come online within the next 10 years. The start-up dates for many of the deepwater oil projects have been pushed back, which has mainly been attributed to regulatory uncertainty. The regulatory uncertainty has also resulted in the decline in deepwater exploration activity since 2007.

There are several planned upstream deepwater projects that are expected to increase Nigerian oil production in the medium term, but the development of these projects depends largely on the passing of the PIB and the fiscal/regulatory terms it provides the oil industry. According to PFC Energy, deepwater exploration activity in Nigeria has declined since 2007 because of regulatory uncertainty, increasingly unfavorable operating conditions, and the delay of the PIB. As a result, while it typically took about 9 years for projects to come online after discovery, the new projects in Nigeria are expected to take closer to 15 years, according to PFC Energy.

Recent drafts of the PIB have also prompted questions about the commercial viability of deepwater projects under the proposed changes to fiscal terms. Deepwater projects have typically included better fiscal terms than onshore/shallow water projects, but the PIB, if passed into law, is expected to increase the government's share of production revenue, particularly during periods of high oil prices, according to PFC Energy. Currently, deepwater projects in Nigeria have an average full-cycle breakeven of $44 per barrel, which ranks among the lowest cost developments, according to PFC Energy. This breakeven price may be affected by the PIB, if it becomes law.

| Operator | Project | Liquids (bbl/d) | Natural gas (MMcf/d)1 | Est. Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chevron | Olero Creek Restoration Project | 48 | na | 2013-2014 |

| Chevron | Escravos Gas to Liquids Plant | 33 | na | 2014 |

| Chevron | Dibi Long-Term Project | 70 | na | 2016 |

| Chevron | Sonam Field Development | 30 | 215 | 2016 |

| Chevron | Nsiko | na | na | 2017+ |

| Eni | Zabazaba-Etan | 120 | na | 2015-2016 |

| ExxonMobil | Etim/Asasa Pressure Maintenance | 50 | na | 2013-2015 |

| ExxonMobil | Bosi | 140 | 260 | 2016+ |

| ExxonMobil | Erha North Phase 2 | 60 | na | 2016+ |

| ExxonMobil | Satellite Field Development Phase 2 | 80 | na | 2016+ |

| ExxonMobil | Uge | 110 | 20 | 2016+ |

| Shell | Bongo Northwest | 40 | na | 2014 |

| Shell | Bongo North | 100 | 60 | 2016+ |

| Shell | Bongo Southwest (Aparo) | 225 | 15 | 2016+ |

| Shell | Forcados Yokri Integrated Project 2 | 90 | na | 2015-2016 |

| Shell | Southern Swamp Associated Gas 2 | 85 | na | 2015-2017 |

| Total | Usan Future Phases | 50 | na | 2016+ |

| Total | Egina | 200 | na | 2017+ |

|

1MMcf/d is million cubic feet per day. |

||||

Crude oil and condensate exports

Europe is the largest regional importer of Nigerian oil. In 2012, Europe imported 889,000 bbl/d of crude oil and condensate from Nigeria, accounting for 44% of total Nigerian exports.

In 2012, Nigeria exported between 2.2 million to 2.3 million bbl/d of crude oil and condensate, according to an analysis of data from EuroStat, APEX Tanker Data, and FACTS Global Energy. The United States has been the largest importer of Nigerian crude oil for at least the past decade. In 2012, the United States imported 406,000 bbl/d of crude oil from Nigeria, accounting for 18% of Nigeria's total exports. India (12%), Brazil (8%), Spain (8%), and the Netherlands (7%) made up the remaining top five largest recipients of Nigerian oil. By far, the largest regional importer of Nigerian oil was Europe, importing 44% of the total in 2012.

U.S. imports

For the past decade, the United States imported between 9% to 11% of its crude oil from Nigeria. However, this share fell to an average of 5% in 2012 and 4% from January to August 2013. As a result, Nigeria has fallen from being the fifth largest foreign oil supplier to the United States in 2011 to eighth in 2013.

Nigeria is an important oil supplier to the United States, but the absolute volume and the share of U.S. imports from Nigeria has fallen substantially. The United States imported 406,000 bbl/d of crude oil from Nigeria in 2012, the lowest volume since 1986 and an almost 50% drop from the average volume imported in 2011. Nigeria fell from being the fifth largest foreign oil supplier to the United States to the sixth in 2012, following Canada, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Venezuela, and Iraq. The trend continued in 2013. EIA data from January to August 2013 show that the United States imported an average of 293,000 bbl/d of crude oil from Nigeria, accounting for slightly less than 4% of total U.S. crude oil imports. During that time period, Nigeria was the eighth largest foreign oil supplier to the United States.

The growth in U.S. light, sweet crude oil production from the Bakken and Eagle Ford has resulted in a sizable decline in U.S. imports of crude grades of similar quality, such as Nigeria's crude oil. Also, not only has the absolute volume of U.S. imports of Nigerian crude fallen, but also the share. According to an EIA article published in April 2012, Nigeria crude as a share of U.S. imports has fallen as a result of the idling in late 2011 of two refineries on the East Coast, which were significant buyers of Nigerian crude, and reduced imports by refiners on the Gulf Coast. The two refineries have since reopened, but they are primarily using domestically produced liquid fuels.

As United States imports of Nigerian oil decreased over the past few years, European imports increased. European imports of Nigerian crude increased by more than 40% in both 2011 and 2012 and were 626,000 bbl/d and 889,000 bbl/d, respectively. Europe is by far the largest regional importer of Nigerian oil.

Refining

Nigeria has a crude oil distillation capacity of 445,000 bbl/d. Despite having a refinery nameplate capacity that exceeds domestic demand, the country must import petroleum because refinery utilization rates are low.

Nigeria consumed 270,000 bbl/d of petroleum in 2012. The country has four refineries (Port Harcourt I and II, Warri, and Kaduna) with a combined crude oil distillation capacity of 445,000 bbl/d, according to OGJ. The refineries chronically operate below full capacity because of operational failures, fires, and sabotage mainly on crude pipelines feeding refineries. Refinery utilization rates have fallen from 65% to 18% in recent years, according to IHS CERA. As a result, the country must import petroleum although its refinery nameplate capacity exceeds domestic demand. According to the OPEC 2013 Statistical Bulletin, Nigeria imported slightly more than 84,000 bbl/d of petroleum products in 2012.

For several years, the government has planned the construction of new refineries, but the lack of financing and government policies on fuel subsidies have caused delays. A Nigerian company, the Dangote Group, plans to construct a $9 billion, 400,000-bbl/d refinery in Nigeria's Ondo state. Dangote plans to contribute $3.5 billion of its equity, seek $ 2.2 billion from export credit agencies and development funds, and finance the remainder with loans from international and local banks, according to IHS CERA. Plans for the refinery complex include petrochemical and fertilizer plants. The expected start date is 2016. If the refinery is built, it will be the largest in Africa.

As part of the PIB energy sector reforms, the government plans to liberalize domestic fuel prices and privatize the refining sector, both of which are controversial topics. Nigerian oil workers' unions have announced plans to oppose the privatization of the existing four refineries and may launch protests against privatization plans, according to IHS CERA.

Fuel subsidiesAccording to an article from Brookings, Nigeria's fuel subsidy cost $8 billion in 2011, accounting for 30% of the government's expenditure, about 4% of GDP, and 118% of the capital budget.

On January 1, 2012, the Nigerian government removed the federal government fuel subsidy on the grounds that it caused market distortions, encumbered investment in the downstream sector, supported economic inequalities (as rich fuel-importing companies were the main beneficiaries), and created a nebulous channel for fraud. However, the government quickly reversed course about two weeks later and reinstated a partial subsidy as public outcry and massive strikes organized by oil and non-oil unions threatened to shut down oil production. Many Nigerians consider the fuel subsidy a key benefit of living in the oil-rich country.

Controversy over Nigeria's fuel subsidy program resurfaced shortly after

the partial removal, and there have been government-led investigations into

corruption and mismanagement. A report by a Presidential Commission put the

revenue losses associated with embezzlement and mismanagement of the fuel

subsidy program at about $1.1 billion. Tensions between Nigerian fuel

importers and the government were also high because the government launched

an investigation of the industry to mitigate subsidy mismanagement. The

investigation led to the arrest of several marketers and the suspension of

companies that were accused of siphoning funds and inflating prices.

Natural gas

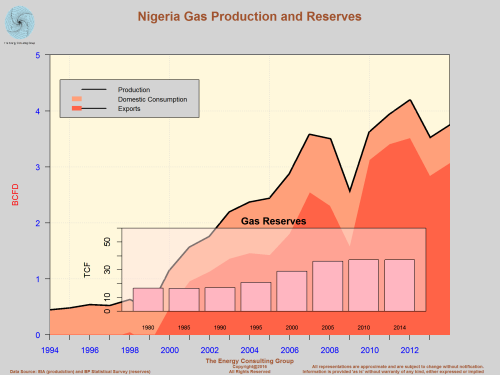

Nigeria is the largest holder of natural gas proven reserves in Africa and the ninth largest holder in the world. Nigeria produced 1.2 Tcf of dry natural gas in 2012, ranking it as the world's 25th largest natural gas producer. Natural gas production is restricted by the lack of infrastructure to monetize natural gas that is currently being flared.

Nigeria had an estimated 182 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of proven natural gas reserves as of January 2013, according to OGJ, making Nigeria the ninth largest natural gas reserve holder in the world and the largest in Africa. Despite holding a global top-10 position for proven natural gas reserves, Nigeria produced about 1.2 Tcf of dry natural gas in 2012, ranking it as the world's 25th largest dry natural gas producer. The majority of the natural gas reserves are located in the Niger Delta. The natural gas industry is also affected by the same security and regulatory issues that affect the oil industry.

Nigeria established a Gas Master Plan in 2008 that aimed to reduce gas flaring and monetize gas resources for greater domestic use and to export regionally and internationally. Draft proposals of the PIB also include these goals. There are a number of recently developed and upcoming natural gas projects that are focused on monetizing natural gas that is flared. These projects are discussed in the Gas Flaring section below.

Dry natural gas production grew for most of the past decade until Shell declared a force majeure on gas supplies to the Soku gas-gathering and condensate plant in November 2008. Shell shut down the plant to repair damages to a pipeline connected to the Soku plant that was sabotaged by local groups siphoning condensate. The plant reopened nearly five months later, but was shut down again for most of 2009 for operational reasons. The Soku plant provides a substantial amount of feed gas to Nigeria's sole LNG facility. As a result, its closure led to a reduction in Nigeria's natural gas production, particularly from Shell's fields in the Niger Delta, and a decline in LNG exports in 2008 and 2009.

Natural gas production gradually grew after 2009, and it reached its

highest level of 1.2 Tcf in 2012. Typically, most of Nigeria's dry natural

gas production is exported in the form of LNG, with smaller volumes exported

regionally via the West African Gas Pipeline. Nigeria consumed 224 Bcf of

dry natural gas in 2012, less than 20% of its total production.

Gas flaring

Nigeria flares the second largest amount of natural gas in the world, following Russia. Natural gas flared in Nigeria accounts for 10% of the total amount flared globally. Gas flaring in Nigeria has decreased in recent years, from 575 Bcf in 2007 to 515 Bcf in 2011. There are a number of recently developed and upcoming natural gas projects that are focused on monetizing natural gas that is flared.

Because some of Nigeria's oil fields lack the infrastructure to capture the natural gas produced with oil, known as associated gas, much of it is flared (burned off). According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Nigeria flared slightly more than 515 Bcf of natural gas in 2011 - or more than 21% of gross natural gas production in 2011. Natural gas flared in Nigeria accounts for 10% of the total amount flared globally.

The amount of gas flared in Nigeria has decreased in recent years, from 575 Bcf in 2007 to 515 Bcf in 2011. According to Shell, one of the largest gas producers in the country, the impediments to decreasing gas flaring has been the security situation in Niger Delta and the lack of partner funding that has slowed progress on projects to capture associated gas. The company recently reported that it was able to reduce the amount of gas it flared in 2012 because of improved security in some Niger Delta areas and stable co-funding from partners that allowed Shell to install new gas-gathering facilities and repair existing facilities damaged during the militant crisis of 2006 to 2009. Shell also plans to develop the Forcado Yokri Integrated Project and the Southern Swamp Associated Gas Gathering Project to reduce gas flaring.

Other recently developed or upcoming gas projects include: the Escravos Gas-to-Liquids plant, Brass LNG, Escravos gas plant development, Sonam field development, Onshore Asset Gas Management project, Assa-North/Ohaji South development, Gbaran-Ubie, the Idu project, and the Tuomo gas field.

The Nigerian government has been working to end gas flaring for several years, but the deadline to implement the policies and fine oil companies has been repeatedly postponed, with the most recent deadline being December 2012. In 2008, the Nigerian government developed a Gas Master Plan that promoted investment in pipeline infrastructure and new gas-fired power plants to help reduce gas flaring and provide much-needed electricity generation. However, progress is still limited as security risks in the Niger Delta have made it difficult for IOCs to construct infrastructure that would support gas monetization.

Gas-to-liquids (GTL)

A Chevron-operated Escravos GTL project is currently underway. Chevron (75%) and NNPC (25%) are jointly developing the $9.5 billion facility. Sasol Chevron, a joint venture between South Africa's Sasol and Chevron, provided technical expertise to design and develop the GTL plant. The project is expected to be operational within a year. The project will convert 325 MMcf/d of natural gas into 33,000 bbl/d of liquids, principally synthetic diesel, to supply clean-burning, low-sulfur diesel fuel for cars and trucks, according to Chevron.

Exports

Nigeria exported 19.8 MMtpa (950 Bcf) of LNG in 2012, accounting for more than 8% of globally traded LNG and making Nigeria the world's fourth largest LNG exporter. Japan is the largest importer of Nigerian LNG, receiving 24% of the total in 2012. The United States did not import any natural gas from Nigeria in 2012 for the first time in more than 10 years.

Nigeria exports the vast majority of its natural gas in the form of LNG, and a small amount is exported via the West African Gas Pipeline (WAGP) to nearby countries. The pipeline was shut down from August 2012 to July 2013 for repairs. The pipeline had been severed by a ship's anchor in the Togolese waters, according to the pipeline's operator. As a result, natural gas exports via WAGP fell from 29 Bcf in 2011 to 14 Bcf in 2012.

Nigeria exported 19.8 MMtpa (950 Bcf) of LNG in 2012, according to FACTS Global Energy, making Nigeria the fourth largest LNG exporter in the world. Nigeria's LNG exports accounted for more than 8% of globally traded LNG. Japan is the largest importer of Nigerian LNG and imported 24% of the total in 2012, followed by Spain (19%), France (12%), South Korea (9%), and India (7%).

Trade patterns for Nigerian LNG have changed over the past few years. Most notably, Nigeria's LNG exports to Europe have decreased significantly. In 2010, Europe imported around 67% of total Nigerian LNG exports, but in 2012, that share dropped to 43%. Nigeria has increased its LNG exports to Asia, namely Japan, following the Fukushima nuclear incident in March 2011. In 2012, Japan imported 4.8 MMtpa (229 Bcf) of LNG, seven times that of the 0.63 MMtpa (30 Bcf) imported in 2010, according to FACTS Global Energy. For the first time since 1999, the United States did not import LNG from Nigeria in 2012, mostly as a result of growing U.S. domestic production.

Bonnny LNG facilityThe Nigeria NLNG facility on Bonny Island is Nigeria's only operating LNG plant. NLNG partners include NNPC (49%), Shell (25.6%), Total (15%), and Eni (10.4%). NLNG currently has six liquefaction trains and a production capacity of 22 MMtpa (1,056 Bcf/y) of LNG and 4 MMtpa (80,000 bbl/d) of liquefied petroleum gas. A seventh train is under construction to increase the facility's LNG capacity to more than 30 MMtpa (1,440 Bcf/y).

Planned: Brass LNG facilityBrass LNG Limited, a consortium made up of NNPC (49%), Total (17%), ConocoPhillips (17%), and Eni (17%), is developing the Brass LNG Liquefaction Complex. The LNG facility is expected to have two liquefaction trains with a total capacity of 10 MMtpa (480 Bcf/y) and a loading terminal. The project is in its engineering phase.

West African Gas PipelineNigeria exports a small amount of its natural gas via the West African Gas Pipeline (WAGP). The pipeline is operated by the West African Gas Pipeline Company Limited (WAPCo), which is owned by Chevron West African Gas Pipeline Limited (36.7%), NNPC (25%), Shell Overseas Holdings Limited (18%), Takoradi Power Company Limited (16.3%), Societe Togolaise de Gaz (2%), and Societe BenGaz S.A. (2%).

The 420-mile pipeline carries natural gas from Nigeria's Escravos region to Togo, Benin, and Ghana, in which it's mostly used for power generation. WAGP links into the existing Escravos-Lagos pipeline and moves offshore at an average water depth of 35 meters. According to Chevron, the pipeline has the nameplate capacity to export 170 MMcf/d of natural gas, although its actual throughput is lower.

Proposed: Trans-Saharan Gas PipelineNigeria and Algeria have proposed plans to construct the Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline (TSGP). The 2,500-mile pipeline would carry natural gas from oil fields in Nigeria's Delta region to Algeria's Beni Saf export terminal on the Mediterranean Sea and is designed to supply gas to Europe. In 2009, NNPC signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Sonatrach, the Algerian national oil company, to proceed with plans to develop the pipeline. Several national and international companies have shown interest in the project, including Total and Gazprom. Security concerns along the entire pipeline route, increasing costs, and ongoing regulatory and political uncertainty in Nigeria have continued to delay this project.

Electricity

Nigeria has one of the lowest net electricity generation per capita rates in the world. Electricity generation falls short of demand, resulting in load shedding, blackouts, and a reliance on private generators. Nigeria is in the process of privatizing the state-owned Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN) in hopes that it will lead to greater investment and increased power generation.

According to Nigeria's August 2013 Roadmap for Power Sector Reform, Nigeria's generation capacity was around 6,000 Megawatts (MW) in 2012, of which 4,730 MW (79%) was from fossil fuel sources and 1,270 MW (21%) was from hydro sources. Generation capacity is projected to have increased to 6,579 MW by the end of 2013, according to the August 2013 Roadmap. Net electricity generation was almost 26 billion kilowatthours in 2011, according to EIA's latest estimates.

Nigeria has one of the lowest net electricity generation per capita rates in the world. According to 2010 World Bank data, 50% of the people in Nigeria do not have access to electricity. Because power generation falls short of demand, this results in load shedding, blackouts, and a reliance on private generators. According to a 2010 Harvard paper, more than 30% of electricity is produced by dirty and inefficient private generators. Businesses often purchase costly generators to use as back-up during outages. Also, the majority of Nigerians use traditional biomass, such as wood, charcoal, and waste, to fulfill household energy needs, such as cooking and heating.

The electricity shortage is attributed to lack of investment in new power infrastructure and also gas supply infrastructure to capture the natural gas that is currently being flared. According to a World Bank report, Nigeria experienced power outages on average for 46 days per year from 2007-2008, and outages lasted almost six hours on average. Population growth coupled with underinvestment in the electricity sector has led to increased power demand without any significant increases in capacity. Inadequate maintenance, insufficient fuel, and an inadequate transmission network also contribute to the problems plaguing the electricity sector.

Nigeria plans to increase generation from fossil fuel sources to more than 20,000 MW by 2020. The Nigerian government has set several targets to increase power generation over the past decade, but none of these targets have been met. The National Integrated Power Project (NIPP) was initially established in 2004 by the Nigerian government as a plan to construct multiple natural gas-fired power plants using natural gas that was flared. Although progress has been slower than initially expected, some of the power plants are expected to come online in the short term. According to the August 2013 Roadmap, NIPP projects currently contribute more than 1,000 MW to the national grid capacity, and it is expected to reach 4,771 MW in 2015 when all planned units are expected to be completed and commissioned. A major source of capacity expansions is expected to come from Independent Power Projects (IPPs). IPPs currently contribute around 1,674 MW to the national grid capacity, and capacity from IPPs is expected to grow to about 14,000 MW by 2020, according to the August 2013 Roadmap. IPPs include power plants operated by IOCs.

Nigeria plans to increase hydroelectricity generation capacity to 5,690 MW by 2020, quadrupling the capacity from the 2012 level. The country plans to increase hydroelectricity generation by upgrading current hydroelectricity plants and constructing new plants: Gurara II (360 MW), Zungeru (700 MW) and Mambilla (3,050 MW). In late 2013, the Nigerian government announced a $1.3 billion deal with China to build the 700-MW Zungeru hydropower project. The Export-Import Bank of China will cover 75% of the cost, while the Nigerian government will finance the remaining cost.

Nigeria is privatizing the state-owned Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN) in hopes that it will lead to greater investment and increased power generation. PHCN was initially established following the Electric Power Sector Reform Act of 2005 and replaced the National Electric Power Authority (NEPA). The PHCN was made of 6 generation and 11 distribution companies. In late 2012, companies run by PHCN were put on sale for a total of $2.5 billion.

On September 30, 2013, the Nigerian government relinquished ownership of

15 electricity companies under PHCN (5 generation and 10 distribution). The

purchasing companies, which are a mix of local and international, are

expected to take physical ownership of the infrastructure. Nigeria's two

remaining state-owned electricity companies under PHCN are expected to be

sold within the following six months, according to an article by Reuters.

NIPP power plants are also expected to be sold to private investors in 2014.

Notes

- Data presented in the text are the most recent available as of December 30, 2013.

- Data are EIA estimates unless otherwise noted.

Sources

Afroil: Africa Oil and Gas Monitor (Newsbase)

APEX Tanker Data

BBC News

BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2011

Brass LNG Limited

Business Monitor International

CIA World Factbook

Chevron

Economist

Energy Intelligence Group

Eni

Eurasia Group

EuroStat

ExxonMobil

FACTS Global Energy

Financial Times

Global Trade Atlas

Harvard- Nigeria: The Next Generation

IHS Cera

IHS Global Insight

International Energy Agency

International Maritime Organization

International Monetary Fund

New York Times

Nigeria LNG Limited

Oil and Gas Journal

OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin

Petroleum Africa

Petroleum Economist

Petroleum Intelligence Weekly

PFC Energy

Reuters

Rigzone

Shell

Total

U.S. Energy Information Administration

West African Gas Pipeline Company Limited

World Bank

|

E&P News and Information Scandinavian International and National International Energy

Agency Department of Trade and Norwegian

Petroleum Ministry of Industry

and E&P Project Information |

|---|